Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings - Museum of Fine Arts

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings - Museum of Fine Arts

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings - Museum of Fine Arts

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

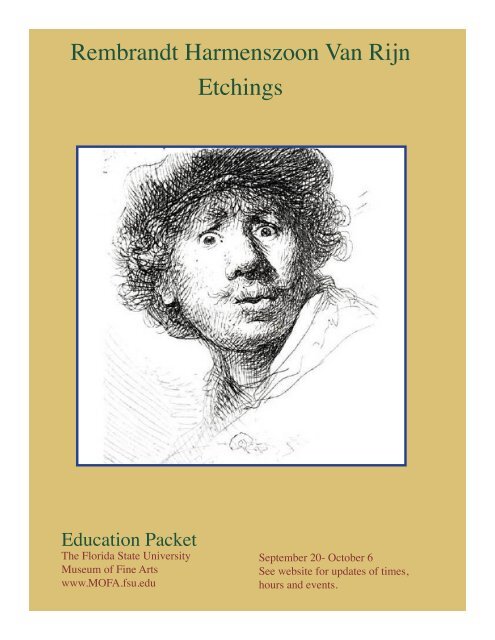

<strong>Rembrandt</strong> <strong>Harmenszoon</strong> <strong>Van</strong> <strong>Rijn</strong><strong>Etchings</strong>Education PacketThe Florida State University<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>www.MOFA.fsu.eduSeptember 20- October 6See website for updates <strong>of</strong> times,hours and events.

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<strong>Rembrandt</strong> <strong>Harmenszoon</strong> van <strong>Rijn</strong>Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5Focus on Individual Prints:Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11Suggested Art ActivitiesThree Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18RubricGeneral Activity Rubric .............................................................................................................................19AppendixGlossary ....................................................................................................................................................20Content and Image Sources ......................................................................................................................21Evaluation .................................................................................................................................................22Self Portrait with Saskia,1636,Etching4 1/4” x 3 5/8”*All images in this packet are for one time educational use only.Written and edited byAruni Dharmakirthi and Morgan Szymanski.For exhibition tours contact Viki D. Thompson Wylder at 850-644-1299.Cover Image: Self-portrait with a Cap, Open Mouthed, 1630, Etching andburin.

<strong>Rembrandt</strong> was born on July 15, 1606 to Harmen Gerritsz van <strong>Rijn</strong> and Cornelia Willemsdochter van Zuytbrouck.He was the eighth in a family <strong>of</strong> nine children. His parents were members <strong>of</strong> the lower middle class; his father was amiller and his mother was the daughter <strong>of</strong> a baker. Like many people <strong>of</strong> the Dutch lower middle class <strong>of</strong> the time,<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s parents were most likely simple and pious individuals. His mother, it seems, was a strong religious influenceon <strong>Rembrandt</strong> due to the numerous portraits <strong>of</strong> her depicted with either the Bible or praying. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s generation grewup under peaceful conditions. Holland had become a world power and the Twelve-Year Truce with Spain in 1609 markedthe virtual end <strong>of</strong> the long struggle for independence from Spain by the Dutch nation.At the age <strong>of</strong> seven, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> was sent to Latin School in Leyden, and in 1620 he enrolled in the University.However a few months into his university education, <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s parents allowed him to enter the workshop <strong>of</strong> JacobIsaacsz van Swanenburgh, due to their son’s strong inclination for painting. At the end <strong>of</strong> three years he went to PieterLastman’s studio, who became <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s most influential teacher. Later in his young career <strong>Rembrandt</strong> settled inAmsterdam because the Dutch capital was wealthy and a source <strong>of</strong> art patrons. In 1632 he completed the Anatomy Lesson,a work that brought him, at the age <strong>of</strong> 26, initial fame as an accomplished artist. Shortly after the creation <strong>of</strong> the AnatomyLesson, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> gained many pupils who paid a great deal <strong>of</strong> money for the privilege <strong>of</strong> working with a master.<strong>Rembrandt</strong> became engaged to Saskia van Uylenborch, the cousin <strong>of</strong> his friend and art dealer Hendrick vanUylenborch. They married in 1634, and he painted numerous portraits <strong>of</strong> her during their time together. In the early years<strong>of</strong> his marriage <strong>Rembrandt</strong> received many commissions. However his taste for extravagant objects also grew. He wasa collector <strong>of</strong> art and jewels. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s possessions accumulated rapidly, and in 1639 he purchased a large house inJoden-Breestraat. This purchase strained his resources and contributed to his financial collapse. He had four children withSaskia, three <strong>of</strong> which died shortly after birth. The fourth son, Titus, survived but Saskia’s health failed and she died aftereight years <strong>of</strong> marriage. She was only thirty. In the late 1640s <strong>Rembrandt</strong> began a relationship with his maid, HendrickjeSt<strong>of</strong>fels with whom he had a daughter. The couple was unable to marry due to a financial settlement <strong>Rembrandt</strong> linked tothe will <strong>of</strong> Saskia, but the two remained together until St<strong>of</strong>fels death.Towards the end <strong>of</strong> his life <strong>Rembrandt</strong> faced much financial hardship. Public patronage began to dwindle and heeventually sold many items in his art collection to help him survive. Around this time, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> moved to Lauriergracht.His eyesight and health declined, and other than the attention afforded by a few young followers and old friends, he liveda quiet life. Financial troubles continued to haunt the old artist. Lawyers sought money <strong>Rembrandt</strong> had borrowed and theysought the creditors’ right to Saskia’s estate. <strong>Rembrandt</strong> died on thefourth <strong>of</strong> October in 1669. He left behind over 500 images and hisworks can be admired in collections around the world. <strong>Rembrandt</strong> isnow an artist held in high regard alongside masters such as Velazquezand Titian.By: Aruni DharmakirthiBiographySelf -Portrait, Frowning: Bust, 1630, Etching,2 11/16” x 2 1/4”2.

Styles and Influences<strong>Rembrandt</strong> first began his artistic studies under Jacob Isaacsz vanSwanenburgh (1571-1638), who was a history painter. After three years <strong>of</strong>apprenticeship learning about the great Italian masters <strong>of</strong> the Renaissance,<strong>Rembrandt</strong> moved to Amsterdam. Between 1624 and 1625, <strong>Rembrandt</strong>spent 6 months studying under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633). Lastman greatlyinfluenced <strong>Rembrandt</strong> in his compositional style. Also, according to arthistorian Arnold Houbraken (1660-1719) in <strong>Rembrandt</strong> van <strong>Rijn</strong>: Biographyand Chronology, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> studied history, historical veracity, rhetoricalgestures, and textual accuracy under Jan Pynas during this time.It is not clear who taught <strong>Rembrandt</strong> the art <strong>of</strong> etching. It is documented,however, that he made two early etchings <strong>of</strong> an old woman (possiblyhis mother) in the year 1628. <strong>Rembrandt</strong> then developed a wide variety <strong>of</strong>themes for his etchings that were previously foreign to the medium. Theseincluded genre, landscapes, portraits, nudes, as well as scenes from ancienthistory, the Bible, and mythology. He especially enjoyed depicting humanemotion and narrative detail drawn from the Old and New Testaments, asseen in Abraham and Isaac (1645). Landscapes were another favorite printsubject. The most dramatic example <strong>of</strong> this genre is The Three Trees (1643)showcasing the typical rainy Dutch weather.<strong>Rembrandt</strong> also manipulated his tools to create the effects he desired.He used, for example, the V-shaped engraver’s burin on his etchings incombination with the fine etching needle and the thicker dry point needle to create rich pictorial effects. The s<strong>of</strong>t ground,or protective covering, on his plates allowed him to move his needle freely, scribbling marks easily like pencil on paper.He ignored the generic hatching and cross-hatching system and instead used scratches, dashes, and flecks to create gradations<strong>of</strong> texture and tone. He experimented with the darkness <strong>of</strong> lines by immersing some <strong>of</strong> them longer in the acid bathto achieve a deeper “bite.” He also explored the effects <strong>of</strong> dry point lines, which are scratched directly into the surface <strong>of</strong>the copper plate. These lines hold more ink, meaning they create darker and richer effects. On paper, dry point creates thesmooth black textures and opaque shadows <strong>Rembrandt</strong> desired. With his technique, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> achieved a sense <strong>of</strong> spontaneitywhile simultaneously paying close attention to detail.By the 1650s the artist had obscured the line between plate and canvas. He left some <strong>of</strong> the ink, or tone, on thesurface <strong>of</strong> the plate to create a “painted” impression on his prints. An example can be seen through two states <strong>of</strong> TheEntombment (1654). Only the etched lines are visible on the first state <strong>of</strong> the plate whereas he created highlights on thesecond state by leaving a great deal <strong>of</strong> ink on the surface and then wiping it away in certain areas.As in the print <strong>of</strong> The Three Crosses (1653), <strong>Rembrandt</strong> dramatically reworked his prints to create almost entirelynew versions <strong>of</strong> the subject from one “state” to the next. He even sometimes reprinted his works on different paper tocreate different tones, for example on the warm-toned Japan paper.His initial etchings from the early 1630s were fully Baroque in style with their emphasis on lighting. In the1640s, he grew comfortable with the medium and his scenes became open spatially. By the 1650s his easiness gave wayto earthy and solid structures. He focused on miniscule details rather than the overall image as with his early etchings.His later etchings were smaller, focusing on the harmony and balance <strong>of</strong> the scene. In many works, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> captureda spiritual feeling. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s mastery <strong>of</strong> many styles and influences made his etchings retain interest and admiration tothis day.By: Morgan Szymanskiabove: The Small Lion Hunt, 1629, Etching, 6 1/4” x 4 5/8”3.

The Printmaking Process4.Etching is a method <strong>of</strong> engraving. In the traditional etching process, a plate (usually copper) is covered with aprotective coat <strong>of</strong> resin. The artist scratches the desired design through the resin with a needle and then immerses the platein a bath <strong>of</strong> acid that “bites” the metal wherever the resin has been removed. Once the plate is taken out <strong>of</strong> the acid, theground, the protective coat <strong>of</strong> resin, is removed with a solvent. The entire plate is then inked and the artist uses cloth topush the ink into the newly engraved lines. The surface <strong>of</strong> the plate is wiped clean with a piece <strong>of</strong> tarlatan, a stiff fabriclike newsprint paper, leaving only the incised lines with ink in them. A damp piece <strong>of</strong> paper is positioned above the plateand together they are run through a press. The design transfers to the paper, making a finished print. It took years <strong>of</strong>experimenting and perfecting the process to add variety to this technique.Although <strong>Rembrandt</strong> adopted this type <strong>of</strong> printmaking, the basic process <strong>of</strong> etching was originated in the early16th century by Daniel Hopfer (c.1470-1536) in Augsburg, Germany. Hopfer first used the technique to decorate armorbefore applying it to fine prints. Then, the French printer Jacques Callot (1592-1635) improved Hopfer’s technique.Callot invented the echoppe, a needle witha slanted oval tip at the end, to create thesame “swelling” line engravers could do.He improved the waxy ground formula forthe copper plate. The improved formulahelped to create deeper lines and extend thelifespan <strong>of</strong> the plate. He also developed the“stopping out” process in which the artistapplies a varnish or other covering to theplate with a brush to keep the acid from theparts already sufficiently corroded, whileallowing the acid to act on the other parts.This creates shaded areas. Callot’s advancementsset the stage for the artist manyconsider the greatest etcher <strong>of</strong> all time,<strong>Rembrandt</strong>.<strong>Rembrandt</strong> (1606-1669) was anartist <strong>of</strong> many talents. He is most famousfor work in several media including hisetchings. He started etching around 1626 when he was 20 years old. One <strong>of</strong> his earliest surviving prints was Rest on theFlight to Egypt (1645). About three years after he published his first etching, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> became a master in his own right.He took several years to finish each plate. Since copper could be easily manipulated he could pound out or add lines, andhe <strong>of</strong>ten made multiple versions <strong>of</strong> each print. He ignored the fact that the image on the plate is reversed when completedbecause he was more concerned with quality than accuracy. For example, some <strong>of</strong> his self-portraits show him left-handedwhen he was right-handed, and his signature was sometimes backwards. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s attention to detail nurtured theexcellence <strong>of</strong> his skills in capturing light, shadow, and depth. He produced over 290 plates in his lifetime. Only 79 are stillin existence today.One <strong>of</strong> his most famous etchings is Christ Healing the Sick better known as the Hundred Guilder Print (1649).The nickname <strong>of</strong> this masterpiece refers to the large amount <strong>of</strong> money someone allegedly paid for it in the mid 1600s. Aswith many <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s works, he referenced a biblical scene. This print relayed a series <strong>of</strong> episodes from chapter 19 <strong>of</strong>the Gospel <strong>of</strong> Saint Matthew. After working on the plate for several years, the final product featured Christ’s calm figure.The right side <strong>of</strong> the etching showed a crowd following Christ. Pharisees were placed in the background. To the left <strong>of</strong> thefigure <strong>of</strong> Peter, a wealthy young man and a silhouette <strong>of</strong> a camel in the doorway referenced Christ’s pronouncement, “Itis easier for a camel to go through the eye <strong>of</strong> a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom <strong>of</strong> God” (Matthew,19:24). Besides rendering scripture, this print exemplified <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s diverse range <strong>of</strong> print styles and techniques. Thegroup <strong>of</strong> figures to the left was created with lightly bitten lines, whereas the right half <strong>of</strong> the etching displayed a richness

due to an experiment with a mezzotint technique. He also varied the appearance <strong>of</strong> the scene by manipulating ink on thecopper plate. In different print runs he used other types <strong>of</strong> paper.The practice <strong>of</strong> etching has evolved over the ages to become one <strong>of</strong> the most preferred printmaking techniques.The malleability and inventiveness <strong>of</strong> the medium appealed to many artists, especially <strong>Rembrandt</strong>. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s opennessand excitement about the art <strong>of</strong> etching set the groundwork for other artists during and after his time.By: Morgan SzymanskiLeft: The Shell or Damier, 1650, Etching, 3.8” x 5.1”Above: <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Mill, 1641, Etching, 5.6” x 8.1”5.

Landscape with Three Trees1643, etching, 8 3/8” x 11 1/8”<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s most famous landscape print is Landscape withThree Trees. This work is elaborate. The etching consists <strong>of</strong> flatexpanses <strong>of</strong> field, a cloud-filled sky, and a watery ground, whichserves as a platform for the three trees. The pictorial intricacy <strong>of</strong> theprint’s making was deliberate as evidenced by the etching process;burin use and dry point can be seen. The scene seems inspired by thecountryside around Amsterdam, which <strong>Rembrandt</strong> recorded frequentlybetween 1640 and 1652, after moving into his home in Sint Anthonisbreestraat.The absence <strong>of</strong> site-specific landmarks suggests, ratherthan a specific location, that <strong>Rembrandt</strong> sought to depict the characteristicfeatures <strong>of</strong> the Dutch environment. Scholarship <strong>of</strong> sixteenthand seventeenth century Netherlandish landscapes indicate that artist’swho showed a universal idea <strong>of</strong> the world rather than a specific placeor time <strong>of</strong>ten employed formal and thematic polarities. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’sLandscape with Three Trees articulates this idea with its many contrasts.For example on the left side are dark wind-blown clouds withdiagonals for rain while on the right the sky is bright and open. Theland at the left is low and open with a calm horizon line and <strong>of</strong>fers anopen spatial area while the land at the right is irregular masses withdensely grouped overgrown foliage. Identifying the juxtapositions inthe print allows the viewer to contemplate contrasts such as dark vs.light, and tamed vs. overgrown foliage.6.By: Aruni Dharmakirthi

The Hundred Guilder Print1649, etching, 11” x 15 1/2”This print’s title can be traced to a few years after its creation.It is believed a buyer bought this print for the very expensiveprice <strong>of</strong> its common title, while a later story tells <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rembrandt</strong>buying back the print at an auction for the same price. The HundredGuilder Print, however, depicts a scene that does not reflectthis subsequently applied title. It shows Christ at the center <strong>of</strong> acrowd, engaging in multiple events from the Bible such as healingthe sick, debating with scholars and calling on children to come tohim. This print makes evident the importance <strong>of</strong> religious iconographyfor <strong>Rembrandt</strong> and illustrates various episodes from chapter19 <strong>of</strong> the Gospel <strong>of</strong> St Matthew. In the print the events interpenetratein order to emphasize the underlying meaning <strong>of</strong> the narrativethemes. For example, a wealthy young man is presented at Christ’sfeet in the print; in the gospel Christ meets him much later andelsewhere. <strong>Rembrandt</strong> worked on The Hundred Guilder Print instages in the 1640s. The print demonstrates a range <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’sprintmaking techniques. The figures on the left are depicted withlightly bitten lines while on the right <strong>Rembrandt</strong> employs darkertones. Also a number <strong>of</strong> impressions <strong>of</strong> The Hundred Guilder Printwere done on Japanese paper. <strong>Rembrandt</strong> was among the firstWestern printmakers to use Japanese paper.By: Aruni Dharmakirthi8.

Beggar’s Family at the Door1648, Etching 6 1/2” x 5”However opulent <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s personal life, he still showed a keeninterest in the less fortunate. He <strong>of</strong>ten turned to the subject <strong>of</strong>beggars and owes much to older representations, withsimilarities to depictions by Jacques Callot. In the Beggar’sFamily at the Door, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> employs a traditionalrepresentational pattern. The wife who carries a baby on her backtakes on the role <strong>of</strong> guide and collects the alms given at the door,while the husband and a young child follow at her side. In hisnumerous depictions <strong>of</strong> beggars, <strong>Rembrandt</strong> shows a persistentinterest in people who live insecurely at the fringes <strong>of</strong> society. Hepresents his beggars as fellow human beings who are marked withsuffering and deprivation. His depictions lack the scorn, ridiculeand satire <strong>of</strong>ten seen in images <strong>of</strong> beggars both from the past andby his contemporaries. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s relationship to the beggar isrevealed in the etching Freezing Peasant in which he portrayshimself as the peasant looking miserably out at the viewer. Also intwo etchings, each titled Self-Portrait with Beggars, <strong>Rembrandt</strong>depicts an image <strong>of</strong> himself surrounded by beggars. Thesignificance <strong>of</strong> these pieces allows us to assume he sympathizedwith peasants and sometimes saw himself as an outcast <strong>of</strong> society.10.By: Aruni Dharmakirthi

11.

Objectives:1.Students will understand that nature can serve as an inspiration.2.Students will understand some basic characteristics <strong>of</strong> the geography in the Netherlands compared to aspects<strong>of</strong> geography in America.3.Students will understand the way in which works <strong>of</strong> art describe the landscape from which it is derived.Materials: Pencils, markers, colored pencils, paperActivity Procedure:1. Show landscape scenes <strong>of</strong> the Netherlands, such as <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Three Trees etching.2. Show photographs <strong>of</strong> geography in the Netherlands.3. Talk about the Dutch landscape. Emphasize features <strong>of</strong> the Dutch geography and discuss the relationshipbetween these characteristics and what is being depicted in the photographs and artworks.4. Show landscape scenes <strong>of</strong> America, such as Thomas Cole’s Distant View <strong>of</strong> Niagara Falls.5. Show photographs <strong>of</strong> geography in America.6. Talk about the American landscape. Emphasize features <strong>of</strong> the American landscape and discuss therelationship between these characteristics and what is being depicted in the photographs and artwork.7. Present the geography <strong>of</strong> a nearby state park or area by the school.8. Take a field trip to the area and take pictures. Teachers should take photos dependent on each child’s choice.9. Display the photographs in the classroom. Identify the geographical features <strong>of</strong> each.10. Have each child pick a photo and do artwork based on the photo.11. Display the Dutch and American landscapes previously shown with those completed by the students.12. Conduct a class discussion as described in session activity.Evaluvation:Teachers should adjust the rubric on general activity on page 19.Three Cottages, 1650, Etching, 6 11/16” x 8 7/16”13.

Beggar’s Family at the Door:Canned Food DriveBig Idea: Historical and Global ConnectionsEnduring Understanding 1: Through study in the arts, we learn about and honor othersand the worlds in which they live(d).Benchmark Code: VA.912.H.1.4Benchmark: Apply background knowledge and personal interpretation to discuss cross-cultural connectionsamong various artworks and the individuals, groups, cultures, events, and/or traditions they reflect.Enduring Idea: Throughout history, aspects <strong>of</strong> the art world and artwork have remained the same as well as changed.Essential Question: Artwork, over time, continues to reflect cultural attitudes. What changes in attitudes does artworkshow, as in <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s images <strong>of</strong> the destitute?Session Activity: In this activity, Students will look at various prints depicting beggars by <strong>Rembrandt</strong>, with a focus onthe Beggar’s Family at the Door. The class will then compare and contrast them with depictions <strong>of</strong> beggars by past artistsincluding <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s contemporaries. These works depict feelings toward the less fortunate during the 1600s and can berelated to the feelings and treatment towards the homeless by society-at-large.Begin by looking at prints such as Beggar with a Wooden Leg, Freezing Peasant, and Beggar’s Family. Examinethe way <strong>Rembrandt</strong> treats the subject, and what sort <strong>of</strong> emotions or narrative he is depicting with the imagery. Compare<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s work with images such as Beggar by Jacques Callot (1592-1635), Crippled Beggars by Pieter Bruegel(1525-1569) and The Louse-Ridden Boy by Bartolome Esteban Murillo (1617-1682). Have the students read Oh, theHumanity by Benjamin Genocchio and have a discussion on the attitudetowards the homeless during the 1600s and the way attitudesand treatments towards them have changed or stayed the same. Invitea pr<strong>of</strong>essional working in a shelter to come to talk to studentsabout the lives <strong>of</strong> the homeless today.For this activity, the class will conduct a group project in whichstudents will contact a shelter to find out the needs <strong>of</strong> the organizationand collect money or items to donate: food, clothing, or othernecessary material. Finally students can write or do an artwork asa reflection on the process. After the students have finished theirproject, conduct a class discussion to talk about any aspect <strong>of</strong> theartwork viewed or the process with the shelter.The Pancake Woman, 1635, Etching,4.2” x 3.1”14.

Hundred Guilder Print:Money TalksFlorida Sunshine State StandardBig Idea: Historical and Global ConnectionsEnduring Understanding 2: The arts reflect and document cultural trends and historicalevents, and help explain how new directions in the arts have emerged.Benchmark Code: VA.68.H.2.3Benchmark: Describe the rationale for creating, collecting, exhibiting, and owning works <strong>of</strong> art.Enduring Idea: Throughout history, aspects <strong>of</strong> the art world and artwork have remained the same as well aschanged.Essential Question: In what ways can the study <strong>of</strong> the economics surrounding<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s prints (for example, price and market context) revealshifts in the art market over time?Session Activity: In this activity students will compare and contrast theprices and historical methods <strong>of</strong> marketing artwork during different timeperiods by focusing on <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Hundred Guilder Print.<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Hundred Guilder Print achieved its name due to the100 guilders it cost to buy it in an auction. That is equivalent to nearlydouble the amount the Dutch paid for the island <strong>of</strong> Manhattan in 1626,which translates the sum to a little under $2000 US dollars today. This wasan outrageous amount <strong>of</strong> money to spend on artwork <strong>of</strong> any kind duringthe 17th century. There are no hard facts associated with this transaction.However, the noted <strong>Rembrandt</strong> scholar, Christopher White, supposedlycan trace the origins <strong>of</strong> the title to a print seller named Mariette, who soldan impression <strong>of</strong> the Hundred Guilder Print back to <strong>Rembrandt</strong> himselffor that large amount <strong>of</strong> money (Martens). Students can compare/contrastthis price with other artworks <strong>of</strong> different time periods, such as The Screamby Edvard Munch (1863-1944) or Massacre <strong>of</strong> the Innocents by Rubens (1577-1640).Following this comparison/contrast, students may learn about the differences between an open market andcommissioned works. During the 17th century in the Netherlands, in a new economic environment, the majority<strong>of</strong> artwork was made for a rising middle class who purchased artwork from an open market, as opposed to othercountries in which primarily royalty and the church commissioned artists to depict certain subjects. Students cancompare and contrast the results <strong>of</strong> these two different methods <strong>of</strong> producing an artwork by juxtaposing<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s print with a work commissioned for royalty, for example a painting in Rubens’ Marie de MediciCycle.Today, art in the United States is produced for an open market as it was in the Netherlands during<strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s time. Galleries are a part <strong>of</strong> this market. Students will explore this system by personally contactinggalleries to conduct interviews about gallery practices and prices.16.Above: A Young Woman Reading, 1634, Etching, 5.1” x 4”

Activity Procedure:1. Students will read an article about the Hundred Guilder Print as it was involved in an auction.Suggested articles:“The Hundred Guilder Print”(http://www.artistarchive.com/Artworks/PrintInfo.aspx?ImageId=110&CID=1)“Living the Biblios: The Mystery <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Hundred Guilder Print”(http://livingthebiblios.blogspot.com/2010/06/mystery-<strong>of</strong>-rembrandts-hundred-guilder.html)2. Students will read an article about the price <strong>of</strong> other artworks.Suggested article:“10 Most Expensive Paintings Sold at an Auction”(http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/most-expensive-paintings-top-10.htm)3. Review and discuss prints to be remembered in class from these articles.4. Discuss the idea <strong>of</strong> an open market and commissions. Juxtapose <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s Hundred Guilder Print andRubens’ Marie de Medici Cycle.Note the following:i. Subjectii. Mediumiii. Sizeiv. Purpose <strong>of</strong> the workv. Original collectionvi. The space in which each was to originally be displayed5. Conduct a discussion <strong>of</strong> the open market/gallery system in the United States today. Research names <strong>of</strong> galleriesin Tallahassee and in other cities. Assign gallery names to students. Students will contact the galleries after eachhas developed interview questions for the gallery director and the teacher has approved those questions.6. Students must select a 1st, 2nd, and 3rd choice gallery (in case the gallery does not answer). Students may emailor call the galleries.7. Students will report their findings to the class to give the following information about the open marketsystem:a. Name and location <strong>of</strong> galleryb. Procedure <strong>of</strong> operationsc. Average price <strong>of</strong> an artwork soldd. What is different about this system as opposed to a time involving commissionsEvaluvation:Teachers should adjust the rubric on general activity on page 19.Works Cited:Martens, Ken. “The Hundred Guilder Print.” ArtistArchive.com. Lynn and Ken Martens. Web. 26 March 2013.18.

General Activity RubricArt LessonWork shows stronguse <strong>of</strong> all skills andconcepts4The project is plannedcarefully;understanding <strong>of</strong> mostconcepts andprocedures is shown.Making good use <strong>of</strong>skills and conceptsWork shows someneed to improve use<strong>of</strong> skills and concepts2The project showslittle evidence <strong>of</strong>understanding theconcepts and/orprocedure.Work shows verylittle use <strong>of</strong> skillsand/or conceptsA.Understanding- Lesson objectivesand goals- Project is wellthought out, clear, andutilizes appropriatetechniques, and artelements.3The project is plannedadequately;understanding <strong>of</strong>some concepts andprocedures is shown.1The project shows noevidence <strong>of</strong>understanding theconcepts and/orprocedures.B.Skills and techniques-Craftsmanship-Use and care <strong>of</strong> toolsand materials4Students applied all <strong>of</strong>the skills required andpaid close attention todetail.3Students showed most<strong>of</strong> the skills requiredand the project showsaverageattention to detail.2The student appliedsome <strong>of</strong> the skillsrequired and paid littleattention to detail.1The student appliedfew <strong>of</strong> the skillsrequired and noattention to detail.C.Creations and Communication-Application <strong>of</strong>Elements <strong>of</strong> Art andPrinciples <strong>of</strong> Design4The projectdemonstrates somepersonal expression,logical problemsolving skills andapplication <strong>of</strong> ArtElements andPrinciples <strong>of</strong> Design3The projectdemonstrates anaverage amount <strong>of</strong>personal expression,problem solving andapplication <strong>of</strong> ArtElements andPrinciples <strong>of</strong> Design.2The projectdemonstrates littlepersonal expression,problem solving andapplication <strong>of</strong> ArtElements andPrinciples <strong>of</strong> Design.1The project lacksevidence <strong>of</strong> personalexpression and littleor no evidence <strong>of</strong>problem solving andapplication <strong>of</strong> ArtElements andPrinciples <strong>of</strong> Design.D.Effort-Performance-Time management-Behavior4The student put forththe effort required tocomplete the projectwell and entered intodiscussion; used classtime well, workedindependently.3The student put forththe effort requiredto finish the project;entered intodiscussion; used classtime adequately.2The student put forththe effort required t<strong>of</strong>inish the project; usedclass time adequately;unwilling to enter intodiscussion; requiredsome redirectionor support from theteacher.1The student put forthno effort or the projectwas not completed;class time was notused well; studentdid not enter intodiscussion; requiredconsistent redirectionor support from theteacher.19.

GlossaryCross-hatching – (n.) A pattern or mark made with such lines.Dry point- (n.) A technique <strong>of</strong> engraving, especially on copper, in which a sharp-pointed needle is used forproducing furrows having a burr that is <strong>of</strong>ten retained in order to produce a print characterized by s<strong>of</strong>t, velvetyblack lines.Texture- (n.) The characteristic visual and tactile quality <strong>of</strong> the surface <strong>of</strong> a work <strong>of</strong> art resulting from the wayin which the materials are used.Silhouette- (n.) The outline or general shape <strong>of</strong> something.Polarities- (n.) The presence or manifestation <strong>of</strong> two opposite or contrasting principles or tendencies.Japanese Paper (washi)- (n.) Paper made in Japan using the fibers <strong>of</strong> native plants, such as gampi, kuwakawa(mulberry tree), kozo, mitsumata. It is made by dipping the sieve, usually made <strong>of</strong> bamboo, several times into thepaper pulp at a particular rhythm.Juxtaposition- (n.) An act or instance <strong>of</strong> placing close together or side by side, especially for comparison orcontrast.Iconography- (n.) Symbolic representation, especially the conventional meanings attached to an image orimages.Contemporaries- (adj.) Existing, occurring, or living at the sametime; belonging to the same time.Portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rembrandt</strong> with Broad Hat, 1631,Etching, 6” x 5.1”20.

Content and Image SourcesCONTENT SOURCES:Białostocki, Jan. A New Look at <strong>Rembrandt</strong> IconographyArtibus et Historiae, Vol. 5, No. 10 (1984), pp. 9-19Published by: IRSA s.c.Held, Julius S. A <strong>Rembrandt</strong> “Theme”Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 5, No. 10 (1984), pp. 21-34Published by: IRSA s.c.Kuretsky, Susan Donahue. Worldly Creation in <strong>Rembrandt</strong>’s “Landscape with Three Trees”Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 15, No. 30 (1994), pp. 157-191Published by: IRSA s.c.Mollet, John William. <strong>Rembrandt</strong>. London: Sribner and Welford, 1879.http://www.theartgallery.com.au/ArtEducation/greatartists/rembrandt/about/http://www.carnegiemuseums.org/cmag/bk_issue/1997/mayjun/feat5a.htmhttp://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rembp/hd_rembp.htmhttp://www.rembrandtpainting.net/index.htmhttp://www.oberlin.edu/amam/<strong>Rembrandt</strong>_HundredGuilder.htmIMAGE SOURCES:http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/<strong>Rembrandt</strong>/Printshttp://metmuseum.org/http://www.rembrandtpainting.net/rmbrndt_etchings/ac_rembrandt_etchings.htm21.

EvaluationWas this material adaptable for introduction to your students?All Some NoneDid you feel the packet adequately provided the information and materials on the topics raised by theexhibition?All Some NoneWas the packet presented in an organized manner?All Some NoneWould you like to continue to recieve materials from the FSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>?All Some NoneDid you use any <strong>of</strong> the suggested activities in your classroom?All Some NoneIf so, were they successful?All Some NoneComments or suggestions:The Flute Player, 1642, Etching,4.5” x 5.7”22.Please return to:FSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Room 250 <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> BuildingTallahassee, FL 32306-1140