What do you think?

Rate this book

267 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1931

How strange life can be—someone walks down the street, feels like eating chocolate, goes into a shop and—‘Yes, Madame, here Madame, as you wish Madame’ And there are people everywhere. They can see and hear everything that’s going on, yet nobody seems in the least bothered—as if all this is completely normal. Who’d have believed it!

This distant ringing that has come to us over the waver of the sea is solemn, dense, and hushed to the point of mystery. As if it has been searching for us, lost as we are in the sea and the night, and has found us, and has united us with this church on the earth, now bathed in light, in singing, in praise of the resurrection.

My memories of those first days in Novorossiysk still lie behind a curtain of gray dust. They are still being whirled about by a stifling whirlwind—just as scraps of this and splinters of that, just as debris and rubbish of every kind, just as people themselves were whirled this way and that way, left and right, over the mountains into the sea. Soulless and mindless, with the cruelty of an elemental force, this whirlwind determined our fate.

BOTW

BOTW http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07bb89z

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07bb89z Unrest and anxiety in Moscow as the Bolsheviks gather, but a 'reading tour' of Ukraine offers Teffi and other artists a way out. Time to take the train.. Reader Tracy-Ann Oberman

Unrest and anxiety in Moscow as the Bolsheviks gather, but a 'reading tour' of Ukraine offers Teffi and other artists a way out. Time to take the train.. Reader Tracy-Ann Oberman On the train to Kiev, away from the Bolsheviks. And Gooskin the indefatigable organiser gets the author and others out of various scrapes.

On the train to Kiev, away from the Bolsheviks. And Gooskin the indefatigable organiser gets the author and others out of various scrapes. Arrival in Kiev, with its sunny days and familiar faces, but a scourge of White Russians is approaching. When will Petlyura get here?

Arrival in Kiev, with its sunny days and familiar faces, but a scourge of White Russians is approaching. When will Petlyura get here? On to Odessa, where the author encounters General Grishin-Almazov, sniffer-outer of local bandits, who 'loved literature and theatre'. And wasn't he once an actor?

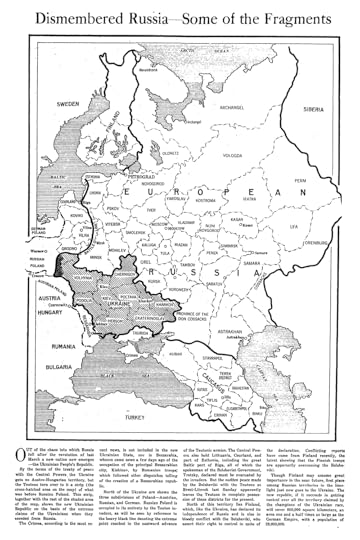

On to Odessa, where the author encounters General Grishin-Almazov, sniffer-outer of local bandits, who 'loved literature and theatre'. And wasn't he once an actor? Sliding down the map, far from Moscow.. the author ends up in Novorossiisk.. where's that? Then she thinks about places even further afield, as the homeland 'slips away from us'.

Sliding down the map, far from Moscow.. the author ends up in Novorossiisk.. where's that? Then she thinks about places even further afield, as the homeland 'slips away from us'. The wonderful thing about Radio 4 is the gift of tasting new books and occasionally one comes across a delight that must be owned in the paper; Memories is such a one. The language, terror of fleeing war, and the relevance to contemporary times cannot be overlooked. Heartily recommended.

The wonderful thing about Radio 4 is the gift of tasting new books and occasionally one comes across a delight that must be owned in the paper; Memories is such a one. The language, terror of fleeing war, and the relevance to contemporary times cannot be overlooked. Heartily recommended.The commissar is indeed terrible. Not a human being, but a nose in boots... a rhinopod. A vast nose, to which there are attached two legs. One leg, evidently, contains the heart, while the other contains the digestive tract. And these legs are encased in yellow lace-up boots... (7)The poet Maximilian Voloshin appears, reciting his famous poetry at authority figures in order to win their influence to save lives, and the colorful yet doomed Kievan politician who bends to his poetic power (112-3).

They say the ocean carries the bodies of the drowned to the shores of South America. Not far from these shores lies the deepest spot in the world - and there, some two miles down, can be found crowds of the dead: fishermen, friends and foes, soldiers and sailors, grandfathers and grandchildren- a whole standing army of the dead. The strong salt water preserves them well, and they sway there gently year upon year. An alien element neither accepts not changes these children of earth.

I close my eyes and gaze into the transparent green water far beneath me...

when we were leaving Moscow: then people had looked at us with real fury - the intelligentsia suspecting we might be from the Cheka while the workers and peasants had seen us as capitalist landlords still drinking their blood.(73)The story of brutal Colonel K and his sadism towards Bolsheviks (218): is this supposed to cheer us as vengeance against the enemy, or an ethnographic look into how war's cruelty spawns further horrors?

Here we are translating khlopotat’, a common Russian word for which there is no English equivalent. Elsewhere, in passages where Teffi draws less attention to this verb, we have translated it in different ways: ‘apply for,’ ‘try to obtain,’ ‘procure,’ etc. In ‘Moscow: the Last Days,’ an article she published in Kiev in October 1918, Teffi explains the word: ‘Incidentally, there is no equivalent to this idiotic term khlopotat’ in any other language in the world. A foreigner will say, ‘I’ll go and get the documents.’ A Russian, ‘I must hurry and start to khlopotat’ with regard to the documents.’ The foreigner will go to the appropriate institution and obtain what he needs. The Russian will go to three people he knows for advice, to two more who can ‘pull strings’, then to the institution—but it’ll be the wrong one—then to the right institution—but he’ll keep on knocking at the wrong doors until it’s too late. Then he’ll start everything all over again and, when he’s finally brought everything to a conclusion, he’ll leave the documents in a cab. This whole process is what is described by the word khlopotat’. Such work, if carried out on behalf of a third party, is highly valued and well paid’

People often complain that a writer has botched the last pages of a novel, that the ending is somehow crumpled, too abrupt.

I understand now that a writer involuntarily creates in the image and likeness of fate itself. All endings are hurried, compressed, broken off.

When a man has died, we all like to think that there was a great deal he could still have done.

When a chapter of life has died, we all think that it could have somehow developed and unfolded further, that its conclusion is unnaturally compressed and broken off. The events that conclude such chapters of life seem tangled and skewed, senseless and without definition.

In its own writings, life keeps to the formulae of old-fashioned novels....

All too quick and hurried, all somehow beside the point....

With my eyes now open so wide that the cold penetrates deep into them, I keep on looking. And I shall not move away. I've broken my vow. I've looked back. And, like Lot's wife, I am frozen. I have turned into a pillar of salt forever, and I shall forever go on looking, seeing my own land slip softly, slowly away from me. (pp. 229-30)

They lived in a wing of a large house. The yard was so densely packed with firewood that you needed a perfect knowledge of the approach channel in order to manoeuvre your way to their door. Newcomers would run aground and, their strength failing, start to shout for help. This was the equivalent of a doorbell and the girls would calmly say to one another, “Lily, someone’s coming. Can’t you hear? They’re in the firewood.”

After I had been there about three days, someone quite large got caught in the trap and began letting out goat-like cries.

I can’t say that the opal brought me any specific misfortune. It’s the pale, milky opals that bring death, sickness, sorrow, and separation. This one simply snatched up my life and embraced it in its black flame - until my soul began to dance like a witch on a bonfire. Howls, screeches, sparks, a fiery whirlwind. My whole way of life consumed, burned to ashes. I felt strange, savage, elated.

I kept the stone for two years and then gave it back to Yakovlev, asking him, if he could, to return it to whoever had brought it to him from Ceylon. I thought that, like Mephistopheles, it needed to trace its steps, to go back the same way it had come - and the sooner the better. If it tried to go any other way, it would get lost and end up in my hands again. Which was the last thing I wanted.

Around the beginning of spring, the poet Maximilian Voloshin appeared in the city. He was in the grip of a poetic frenzy. Wherever I went, I would glimpse his picturesque silhouette: dense, square beard, tight curls crowned with a round beret, a light cloak, knickerbockers, and gaiters. He was doing the rounds of government institutions and people with the right connections, constantly reciting poems. There was more to this than was first apparent. The poems served as keys. To help those who were in trouble Voloshin needed to pass through certain doors - and his poems opened these doors.

[...]

On one occasion I too received a visit of this nature.

Voloshin recited two long poems and then said that we must do something on behalf of the poetess Kuzmina-Karavayeva, who had been arrested (in Feodosya I think), because of some denunciation and was in danger of being shot.

“You’re friends with Grishin-Almazov, you must speak to him straightaway.”

I knew Kuzmina-Karavayeva well enough to understand that any such denunciation must be a lie.

“And in the meantime,” said Voloshin, “I’ll go and speak to the Metropolitan. Karavayeva’s a graduate of the theological academy. The Metropolitan will do all he can for her.”

I called Grishin-Almazov.

“Are you sure?” he responded. “Word of honour?”

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll give the order tomorrow. All right?”

“No, not tomorrow,” I said. “Today. And it’s got to be a telegram. I’m very concerned - we might be too late already!”

“Very well. I will send a telegram. I emphasise the words: I will.”

Kuzmina-Karavayeva was released.

In Novorossiisk, in Yekaterinodar, in Rostov-on-Don - at all the remaining staging posts of our journey - I would again encounter the light cloak, the gaiters, and the round beret crowning the tight curls. On each occasion I heard sonorous verse being declaimed to the accompaniment of little squeals from women with flushed, excited faces. Wherever he went, Voloshin was using the hum - or boom - of his verse to rescue someone whose life was endangered.