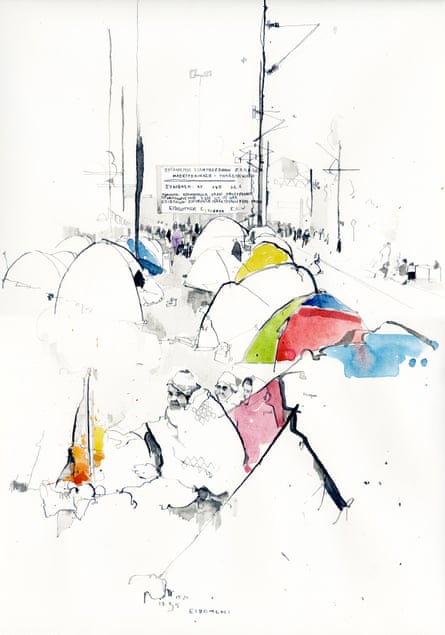

A reportage illustrator specialising in travel and current affairs, George Butler, 33, has worked in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2014 he helped establish the Hands Up Foundation to fund health and education services in Syria. A new exhibition of his work, Anima Mundi: Drawn Stories of Migration, will be at Bankside Gallery, London, 20-25 November. Butler grew up in Oxforshire and is now based in south London.

What is it like trying to draw in the thick of a war zone or humanitarian crisis?

I actually find it quite peaceful in a funny sort of way. You have, in the worst moments, a job to do and a way of distracting yourself. It becomes your way of comprehending what’s going on. And at the beginning, when you’re trying to work out who to speak to, it’s just a wonderful introduction. Lots of stories have led from that moment, where people come and sit next to you and say: “Why don’t you come into my shop?” or “Let me show you round this prison”.

Is it safe to draw in situ, or do you sketch and then finesse it at home?

It’s a bit of both. The best ones are done as much as possible on site. Last year, I was on the frontline with the Golden division in the Iraqi army – that was fine for 45 minutes or an hour on a rooftop, but any longer… Drawing has become a good gauge for whether a place is safe: if I can’t sit and draw for 45 minutes, I might be pushing it too far.

How do you deal with the fear?

I’m not trying to scare myself, or to compete with frontline photographers. Often that question comes with an assumption I must be doing it for an adrenaline rush – I don’t really see it like that. The inspiration comes from sitting down with someone I would otherwise never have met, and having a connection with them.

Are people pleased to be drawn?

People like to tell their story and at the very least it’s a distraction from a difficult life in a refugee camp or a break from the monotony of work. But people think it’s odd, and they ask lots of questions. I sometimes get accused of being a spy…

Do you get interference from authorities?

We were followed in Belarus by the secret service, which was expected. You quite often get someone in Kabul, with a radio and black leather jacket, asking questions, and I was thrown off a train in Uzbekistan. But, by and large, you can travel on a tourist visa as a painter.

Can an artist report on war in a way that a photographer or journalist can’t?

Because you’re almost always doing it by permission of the people around you – they’re watching you as you do it – it’s honest. You can’t make it up at one end and that pays off at the other, when an audience looks at it. The way our news is delivered at the moment, it’s often mistrusted or known to be manipulated, so in a funny sort of way – even through it’s incredibly traditional, and could be made up – drawing carries real weight.

Is it a tradition that’s been lost since the advent of photography?

I think so. Photography is brilliant, but we’ve just become obsessed and addicted to it and forgotten some nice bits of creativity on the way.

Which other artists do you admire?

Most of the illustrators are dead – people like Paul Hogarth and Ronald Searle. Some of the stuff Grayson Perry has done is powerful; he uses his image and art as a platform.

We hear a lot about compassion fatigue. Can art provide a different way to remind people of what’s happening?

I was asked to go to Belarus by Amnesty International to do a project about the death penalty, and I’ve worked for Save the Children in refugee camps in Greece, and for Oxfam in Palestine. For those stories that are not shocking enough to make our front pages visually, art is a brilliant way to re-engage people.

How do you find coming home and getting on with normal life?

It’s quite odd. But although there are moments that are incredibly shocking for any one human brain, in a way, I’m quite positive – very often, the drawings are about life carrying on despite the situation.

Anima Mundi: Drawn Stories of Migration by George Butler is at Bankside Gallery, London, 20-25 November

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion