Originally published 20 March 1989

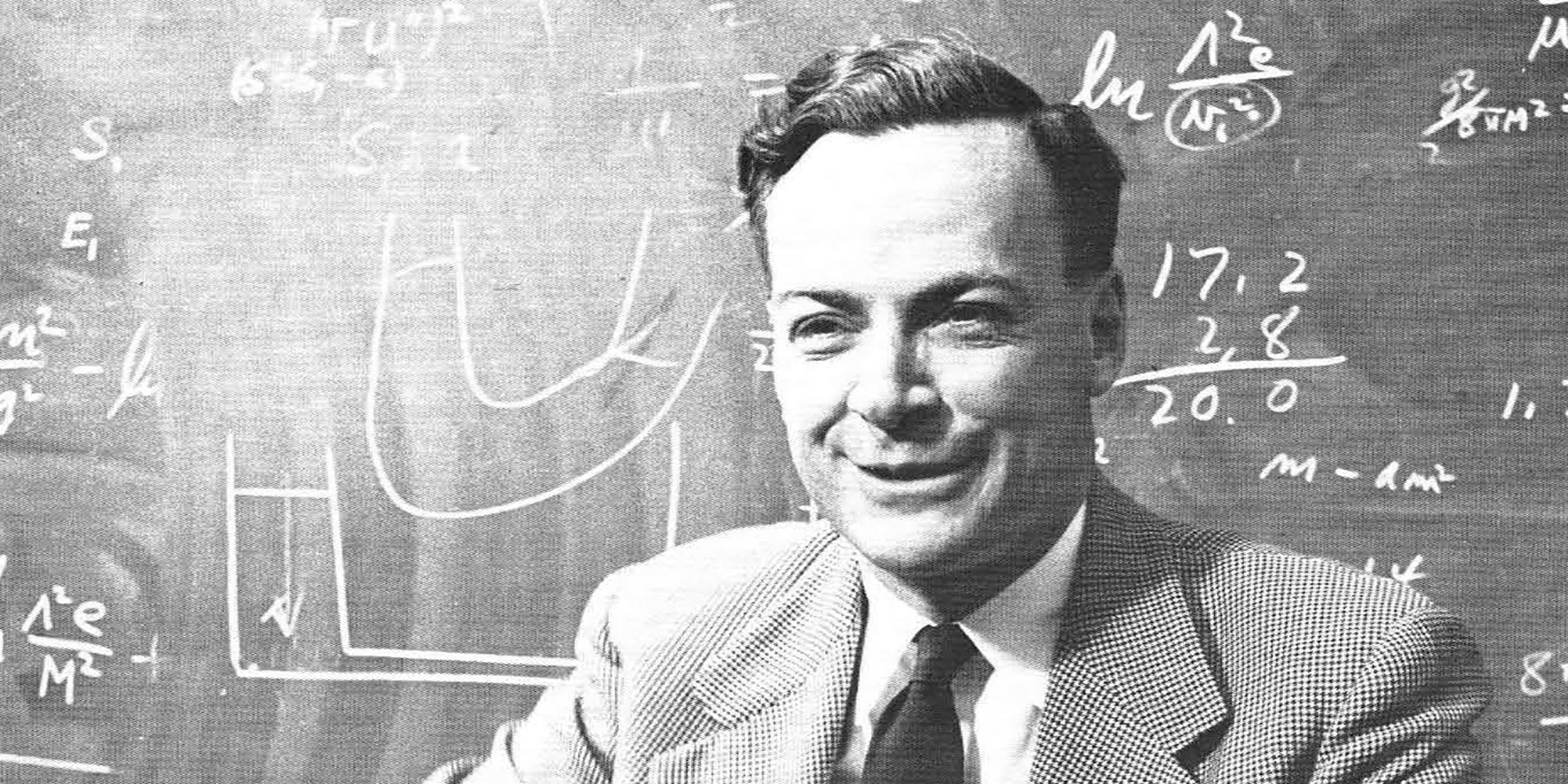

The February [1989] issue of Physics Today has been lying around unread for weeks. It is a special commemorative issue on Richard Feynman, the Nobel prize-winning theoretical physicist who died in 1988 at age 70. I was in no hurry to read it. I saved it until I had the time and inclination for a real bout of nostalgia.

I never met Feynman, although as a UCLA graduate student I sometimes crashed his Caltech lectures. I have no personal anecdotes to relate, such as the many wonderful stories told by colleagues, former students, and friends in the special issue of the physics journal. But Feynman’s influence on my life was considerable, as I am sure it was for many other physics teachers who came to the profession in my generation, and the nature of the influence is worth telling.

The Red Books

I began full-time teaching in 1964. The first volume of The Feynman Lectures on Physics (written with Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands) was published the previous year. Two more volumes followed in short order — three big books (the Red Books, we called them) that were more or less a transcription of a two-year introductory physics course Feynman conducted at Caltech. The books were brilliant, idiosyncratic, and totally unlike any texts that had gone before. They confirmed what I had seen and heard when I sat in on Feynman’s talks; the author was a teacher of surpassing talent.

In the lecture hall, Feynman taught students. In the Red Books he was a teacher of teachers. The Feynman Lectures on Physics were never easy to use as texts. They are too personal, too much one man’s vision of physics, and they assume a student of top Caltech talent, all too rare in the “burbs” of Academe. Feynman hoped to jump-start students into the excitement of contemporary physics, by exposing them early to cutting-edge problems. For the very best student he may have succeeded, but for most students an old-fashioned introduction to classical principles remains the best beginning.

Nevertheless, those of us who began teaching with the Red Books had seen the light, and the light was Feynmanesque razzmatazz. The books were more inspirational than practical, more revelatory than useful. Teaching could be a high art, an exciting art — that was the real message of the books. Many of us who entered the classroom in those day were determined to become “the local Feynman.”

Americans saw a bit of what made Feynman a great teacher during the public hearings on the Challenger explosion. Feynman was appointed to the commission established to ascertain the cause of the disaster. He went straight to the heart of the problem — on television — by dipping a piece of rubber in a pitcher of ice water, demonstrating simply and directly that cold rubber rocket seals are brittle.

In Physics Today, David Goodstein, a physicist and vice provost at Caltech, tells this story of Feynman as teacher: “Once I asked him to explain, so that I could understand it, why spin‑½ particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics. Gauging his audience perfectly, he said, ‘I’ll prepare a freshman lecture on it.’ But a few days later he came to me and said: ‘You know, I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t reduce it to a freshman level. That means we really don’t understand it.’”

Goodstein’s anecdote is a lesson for all teachers: If we can’t explain a thing simply, it probably means we don’t understand it. It was partly Feynman’s knack for explaining complicated things simply, and elegantly, that made The Feynman Lectures on Physics so influential to my generation of teachers. The other part of the equation was wonder.

The Red Books are full of italics. Almost every sentence contains an italicized word or phrase. As one reads, one can almost see Feynman’s animated hands, sly smile, and wry voice accentuate some wonderful aspect of his subject — as when he refers to the human body as a pile of atoms: “When we say a pile of atoms, we do not mean merely a pile of atoms.”

A sense of wonder

For Feynman, nothing was “merely.” Everything was “WOW!” In a New York Times Magazine interview, he gave credit for his keen sense of wonder to his father: “When I was a boy, Dad and I took long walks in the woods and he showed me things I would never have seen by myself… He would say, ‘See this leaf? It has a brown line. Why?’ And when I tried to answer, my father would make me look at the leaf and see whether I was right and then he would point out that the line was made by an insect that devotes its entire life to that project. And for what purpose? So that it could leave eggs to make more insects. My father taught me continuity and harmony in the world. He didn’t know anything exactly, whether the insect had eight legs or a hundred legs, but he understood everything.”

Richard Feyman wedded his father’s sense of wonder to a brilliant gift for theoretical physics. Above all else, he was a teacher. As W. Daniel Hillis, founder of Thinking Machines Corporation in Cambridge, writes in Physics Today, “the act of discovery was not complete for him until he had taught it to someone else.”

Feynman taught a generation of physics teachers how to teach. For those of us who began teaching in his shadow, the shadow was more light than darkness.