American foulbrood

Information about American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae), a serious brood disease of honey bees.

About American foulbrood

American foulbrood (AFB) is caused by a spore-forming bacterium, Paenibacillus larvae, and is a serious brood disease of honey bees. AFB impacts developing honey bee larvae only. It does not affect adult honey bees. AFB spores are very resilient and able to survive heat and other environmental factors. To this point, spores have been found to remain viable on used honey bee equipment for up to 70 years. This disease is highly contagious, will contaminate beekeeping equipment, bees and honey, and will weaken, and in most cases, kill a honey bee colony. AFB may be found at any time of the year in honey bee colonies or in used beekeeping equipment. There is no cure for AFB once a colony has developed an active infection. Beekeepers can take steps to mitigate an infection from establishing itself and manage an infection if present in their beekeeping operation.

Transmission and life cycle

As a spore-forming bacterium, AFB has two major life stages:

- The spore stage is when the bacterial cell becomes dormant and surrounds itself in a strong, spherical shell. Large numbers of spores become imbedded within the wax comb and used beekeeping equipment.

- The vegetative stage is when the spore germinates and becomes an active bacterial cell that grows and multiples. This stage is what kills the honey bee larvae and produces large numbers of spores.

AFB spores are picked up by worker bees from AFB infected honey bee colonies or equipment. Spores contaminate the mouthparts of worker bees and are subsequently fed to developing honey bee brood.

In the brood, spores transform into their vegetative state. The bacterial cells rapidly multiply in the tissues of the larvae, generating billions of new AFB bacterial cells. Honey bee larva infected with AFB die after the brood cell is capped.

The dead larva decomposes into a gooey mass that settles to the bottom of the brood cell and eventually hardens and becomes black in color ("AFB scale"). In this state, AFB bacterial cells have converted to spores. Each brood cell containing scale may contain up to 2.5 billion spores.

Worker bees remove the scale from the wax comb and contaminate their mouthparts with AFB spores. These spores are inadvertently fed to other developing brood in the colony. The cycle repeats with more honey bee brood being infected with AFB resulting in decreased colony population, strength and health.

As the colony weakens, it may be targeted by other honey bee colonies and robbed of its honey stores. Honey containing AFB spores is taken back to the healthy honey bee colony. Spores then carry the infection to honey bee brood in the new colonies.

Signs and symptoms

It is important for beekeepers to familiarize themselves with healthy brood conditions and types of brood disease as all symptoms of AFB are found in the brood nest and used brood comb of the honey bee colony. There are several symptoms that may indicate an AFB infection, but these will vary in their combination depending on the stage of infection.

Discoloured larvae

Healthy larvae are always pearl white (Figure 1). Anytime a larva dies in the cell it becomes discoloured and darkens (Figure 1). Having some larvae death in a colony can be normal, therefore seeing discoloured larvae is not always specific to AFB. Brood infected with AFB will turn from white, to beige, to light coffee brown, to dark coffee brown, then to black as it begins to dry out.

Spotty brood pattern

A healthy, productive colony will produce a solid brood pattern with few empty cells, whereas unhealthy or diseased colonies may have a brood pattern with many missed cells (Figure 2). This characteristic is not always specific to AFB since a spotty brood pattern is common to many colony issues including other brood diseases or a poor or weak queen.

Perforated capping of the brood cell

Perforations of brood cell cappings that appear irregular and are located at the margin of the cappings are likely caused by a brood disease (Figure 3). This characteristic is not always specific to AFB since perforated cappings are seen in other brood diseases, such as chalkbrood, or when brood is damaged from high levels of varroa mites.

Sunken or discoloured wax cappings

Wax cappings are normally slightly convex and light brown in colour. In the presence of an AFB infection, wax cappings will be slightly concave or could have a dark, greasy appearance. These symptoms are not always present in the early stages of AFB.

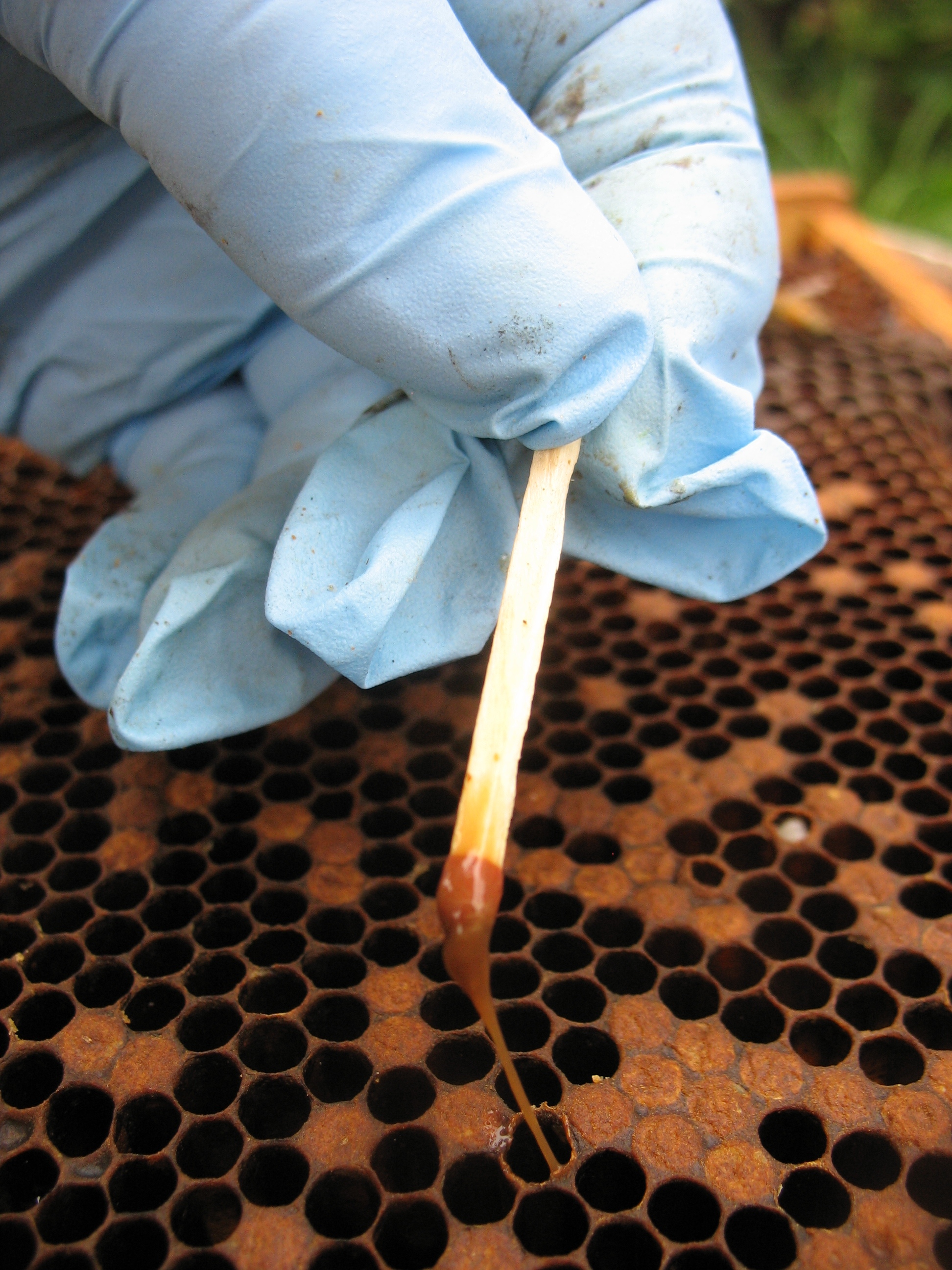

Ropey dead larvae

During one stage of an AFB infection, dead larvae will settle to the bottom of the brood cell and turn into a gooey, mucus-like consistency. This gooey material will stretch out of the cell to a length of 2.5 cm or more (Figure 4). This is commonly called the Ropey Test. Ropey, dead larvae is a specific symptom of AFB and no other brood disease displays this characteristic. Note that AFB will not always display this symptom as it is dependant on the stage of the infection. Early in the infection, the dead larvae will not be gooey enough and in later stages the dead larvae are dried and hardened.

Foul smell

Although other honey bee diseases and issues may be associated with a foul odour, the odour of AFB is quite distinct as a fishy or rotten smell. This attribute may be somewhat subjective as there are some people who can readily detect and identify the smell where others cannot.

Black, hardened scale that adheres to the wall of the wax cell

After an AFB infected larva dies and settles to the bottom of the brood cell it will dry and harden. This black, flat, charcoal-like material stuck to the bottom of the brood cell is a symptom specific to AFB (Figure 5). Dried scale is hard, brittle and cannot be removed from the wax cell without damaging it. The best way to detect AFB scale is to hold the frame with your thumb and index finger and slowly rotate the frame back and forth so the bottom of the frame rotates along a 30° axis (Figure 6). In inspecting the frame in this manner, you will see the dark scale at the bottom of the cell. Good lighting is needed, and if possible, have the sun at your back.

Prevalence and spread

AFB may be found at any time of the year in honey bee colonies, honey or in used beekeeping equipment. AFB spores can survive on used equipment for decades.

Spread of AFB through honey bee activity

Drifting

AFB can spread within a bee yard when honey bees from an infected colony mistakenly enter another colony after returning home from foraging.

Robbing

Robbing occurs when honey bees from one colony collect or rob the honey stores of another colony. It is a natural behaviour of honey bees. In extreme circumstances, where there is a shortage of nectar or weak and/or dead colonies in the surrounding environment, robbing can become quite intense. Robbing can result in the spread of AFB within a bee yard or between different bee yards (up to 8 km away) when AFB spores are transferred with the honey. Robbing is particularly a concern during a nectar shortage.

Spread of AFB through beekeeper activity

Exchanging equipment between colonies

Moving frames of brood between different colonies in a bee yard to equalize colonies or to boost weak colonies is a common and necessary beekeeping practice. However, AFB may be spread from an infected colony to an uninfected colony when this is done. Beekeepers must be mindful of this practice's risk and should be vigilant for any signs and symptoms of the disease.

Feeding contaminated honey or pollen

Honey and pollen obtained from outside sources may contain AFB spores. Honey from outside sources should not be fed to honey bee colonies. If purchasing pollen for the purpose of feeding to honey bees, ensure that the pollen has been irradiated as this practice will render the spores inactive.

Packages

Although not likely to spread AFB, honey bee packages are a potential source of infection. Packages therefore require a federal and/or provincial import permit.

Purchasing infected honey bee colonies or equipment

Selling and purchasing honey bees or used equipment is a common practice in the beekeeping industry. This practice does risk introducing AFB into an operation. It is important that selling beekeepers are diligent in inspecting the brood of their colonies to detect AFB. It is equally important that purchasing beekeepers purchase from permitted sources. Selling beekeepers must have a valid permit issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs’ (OMAFRA) Apiary Program prior to any sales of bees or used equipment taking place. Permits are issued by the ministry’s Apiary Program only after the inspection requirements are met, which helps protect the health of honey bees, particularly from pests and diseases.

Swarms

Swarms may be a source of AFB if the swarm originated from an infected colony. Swarms always pose a risk of transferring pests and diseases since there is no way to be certain of the swarm's origin. However, since a swarm has no brood there is an opportunity to take management steps to minimize AFB risk.

Used beekeeping equipment

Beekeeping equipment that is not properly stored and is in a location accessible to honey bees is a possible source of infection. In most cases, the beekeeper may not be aware the equipment is infected.

Mitigate an infection or outbreak

Beekeepers can take steps to mitigate an AFB infection from establishing itself in their beekeeping operation.

A number of management activities influence the health, production and population of honey bee colonies. Management practices can and will vary depending on the focus of the beekeeping operation (such as honey production, queen and nucleus production, and pollination), but should incorporate basic biosecurity and Essential practices for beekeepers in Ontario (best management practices or BMPs). Good biosecurity practices and basic colony BMPs have been found to be the most effective and practical means of mitigating AFB infections and include:

- familiarizing yourself with the symptoms of AFB and other pathogens of honey bees

- examining your colonies regularly to ensure that they are healthy and disease free, keeping an eye out for the symptoms of brood diseases

- conducting a thorough inspection of the brood nest for brood diseases at least twice a year, in the spring and fall, and before treatment with drugs (such as oxytetracycline) which can mask some symptoms of the disease

- properly store used beekeeping equipment, promptly manage dead colonies in a bee yard, and have equipment inspected before a sale or transfer of ownership

Best management and biosecurity practices when infection is found

- Work with an apiary inspector on steps to address AFB where it is confirmed.

- Do not salvage honey from an infected colony.

- Promptly destroy infected colonies and associated equipment.

- Consider treating non-symptomatic colonies in the yard with an antibiotic (this will depend on the time of year and conditions).

- Do not treat any AFB symptomatic colonies with an antibiotic (promptly destroy symptomatic colonies).

- Monitor the health status of the yard that was positive for AFB on a more frequent basis and be vigilant of AFB in your other bee yards or in the surrounding area.

- Retain all colonies at the AFB-positive bee yard for a period of two years.

Refer to general best management and biosecurity practices for Ontario beekeepers.

Preventative treatment

There is no cure for AFB. However, beekeepers may consider using a prophylactic antibiotic to prevent AFB from establishing itself in their operation. Although antibiotics are not a cure for AFB infections and have no impact on AFB spores, antibiotics may prevent an active infection by inhibiting the development of AFB in the gut of the larvae since it affects the vegetative stage (bacterial cell) of AFB. Thus, the use of antibiotics may prevent AFB from rapidly multiplying within a colony, but once a colony is infected with high levels of spores, treatment with antibiotics is too late.

Antibiotics can be effective at preventing infections from establishing, but they can also suppress the visible symptoms of AFB, thereby masking an infection. For this reason, it is important to inspect colonies before treatment. Beekeepers should also be aware that AFB infections can still take place even when antibiotics have been used. Beekeepers require a prescription from a veterinarian to access antibiotics for their honey bees. For general information on antimicrobial use in agriculture visit the Antimicrobial Resistance in Agriculture webpage. For more specific information on antibiotics for beekeeping in Ontario refer to the Ontario Beekeepers’ Association’s Antibiotic Access Resources for Beekeepers.

Consult the Treatment options for honey bee pests and diseases in Ontario for recommended monitoring methods, treatment methods and timing of treatments for honey bee pests and disease.

If you suspect infection

Finding an AFB infection as early as possible and taking immediate action is critical to prevent its spread within an operation and area.

If signs or symptoms of an AFB infection are observed in a colony (alive or dead), the beekeeper is to immediately contact their local apiary inspector. It is a requirement of the Ontario Bees Act that beekeepers report this disease. An apiary inspector will inspect the colonies to determine if AFB is present and may take a sample for resistant AFB testing.

If you find positive colonies or equipment

If AFB is determined to be present on inspection, all colonies in the yard are to be inspected by an apiary inspector to determine each colony’s AFB status. The inspector will require the beekeeper to take action(s) on the AFB infected colonies and the bee yard within a specified timeframe. Beekeepers can, voluntarily or by inspector Order, take one or all of these actions:

- destroy infected colonies and equipment

- treat non-symptomatic colonies in the yard (this will depend on the time of year and conditions)

- retain all colonies at the bee yard for a period of two years

Treatment of non-symptomatic colonies may prevent these colonies from being infected but comes with no guarantees that these colonies will not also develop an AFB infection and have to be eventually destroyed. Once AFB is present in a yard, regular monitoring of the other colonies for signs and symptoms of an AFB infection is necessary so they too can be destroyed in a timely manner to stop the AFB cycle.

In Ontario, OMAFRA’s Apiary Program maintains a standard practice that non-symptomatic, live colonies from AFB-positive yards must be retained in the yard (that is, not moved from that location), via retainment Order, for a two-year period from the date that AFB was detected. This is done to allow the beekeeper time to control the infection and allow for re-inspection of colonies in the AFB-positive yard. After two years, the retainment Order is lifted if the bee yard undergoes an inspection by an apiary inspector and is assessed to have no AFB present.

Honey supers from non-symptomatic colonies in an AFB-positive yard may leave for extraction but are to be returned to the same bee yard where they originated. These supers should be labelled and harvested separately from other uninfected yards in the operation.

A colony is considered AFB-positive if there are one or more honey bee larvae (fresh or old) within the colony that display signs or symptoms of the disease. All associated equipment that is or was in contact with this colony is considered AFB-positive.

A bee yard is considered AFB-positive when one or more colonies in the yard are AFB-positive.

Destruction of positive colonies, equipment and materials

Immediate destruction of AFB-positive colonies (bees) and equipment (hive box, lid, frames and other associated materials) is critical. The longer an infected colony or equipment is left without being destroyed, the greater the opportunity for AFB to spread to other nearby colonies or bee yards.

Materials to be destroyed are:

- biologicals — all honey bees (larvae, adults), wax comb and the honey crop (honey inside frames). A honey crop from an AFB-positive colony may not be salvaged.

- equipment — all frames (including brood and honey frames), foundation, honey supers and bottom boards within the colony. The only materials that may be disinfected and not destroyed are hive bodies or boxes, queen excluders (if metal) and telescoping lids.

Skipping steps or salvaging materials or equipment that may contain spores increases the likelihood and opportunity that the AFB infection will persist and spread, resulting in more colonies and equipment becoming infected and needing to be destroyed. It is better to destroy one AFB-positive colony properly and early, rather than potentially hundreds of colonies that become infected later because of equipment salvaging.

How to destroy positive colonies, equipment and materials

Destruction by fire is the most common method used, and is the method specified in the Bees Act, for destruction of colonies infected with AFB.

Approval for another destruction method may be considered by the Provincial Apiarist in circumstances where there are large amounts of plastic hive equipment (such as full plastic frames vs. wooden frames with plastic foundation) or where burn restrictions or fire bans are in place. Contact the Provincial Apiarist in writing if consideration for an alternative destruction or disposal method is sought. Other methods (such as burial or irradiation) must be approved by the Provincial Apiarist.

Whatever the approved method, the beekeeper is ultimately responsible for the destruction of AFB-positive colonies, equipment and materials.

1. Preparing colonies for destruction

- Seal bees inside hive.

- Completely block the entrance to the hive and fill any cracks in the hive.

- Complete this activity at a time when the bees are not flying (such as evenings or during rainy weather) and are settled (hives should not be sealed/destroyed immediately after inspecting or disturbing the colony). This practice ensures the bees are all at home in the hive and prevents the bees from the AFB colony relocating to neighbouring colonies and spreading the disease.

2. Immobilizing and killing bees

- Use diesel fuel to immobilize and kill the colony.

- Remove the lid of the hive when the bees are not flying and sprinkle diesel fuel over the colony.

- It may be necessary to split the chambers and add diesel fuel to the lower chamber(s) as well. The amount of diesel fuel needed depends on the size of the hive. It is estimated that:

- 300-500 mL of diesel fuel is needed for a one-to-two story hive

- 1 L of diesel fuel is needed for a three-to-four story hive

- Securely replace the lid on the hive.

- After 10 minutes, check to see if all the adult bees are immobilized. If not, repeat the above process to wet the remaining adult bees.

3. Destruction of positive colonies, equipment and materials by fire

- Obtain a fire permit from the proper authority, be compliant with the law, including all local by-laws, and employ safe burning practices at all times. Note that:

- Diesel fuel is not added as a fire accelerant. Beeswax is extremely flammable and there is sufficient wax in the combs to fuel the fire.

- Hives burn vigorously and flames can reach two to three times the height of the stack.

- Boxes of frames soaked with diesel fuel may explode if put into the fire whole.

- It may take two to three hours to burn a hive and more to burn three to four hives.

- Dig a hole large enough to contain the materials to be burned.

- A hole of 1 m (3 ft) in diameter and at least 30 cm (1 ft) deep is suggested for one hive. Expand the hole accordingly for multiple hives.

- Ensure the hole is deep enough so that any infected material that may not be completely destroyed by fire can be buried so as not to be accessible or found by foraging bees.

- Slope the bottom of the hole to provide a pooling location for unburned honey so that it does not choke out the fire.

- Place the hive(s) and materials to be destroyed about 3 m (9 ft) from the hole.

- To avoid dropping dead bees or honey on the ground, move the hives as a complete unit. Alternatively, individual hive boxes can be moved one by one in an upturned hive lid as this will prevent bees or honey from falling on the ground.

- Start the fire in the empty hole.

- Once the fire is well established, it works best to destroy affected material in the following order:

- Frames

- Place frames with honey around the edge of the fire so not to douse the fire

- Once the honey has run out of the frames, push the frames into the fire

- Bottom boards

- Lids

- All parts of the hive that have diesel fuel on them

- Frames

- Once the fire has burned down to embers, cover the embers and any material that has not fully burnt with the soil from the hole.

- If parts of the hive, that do not have diesel fuel on them, are to be salvaged (such as boxes, telescoping lids and metal queen excluders) they must be well flamed (with a propane torch) before used again.