Anna Laurens Dawes's legacy as an anti-suffragist, was noted by The Eagle in November 1940, when marking the 20th anniversary of the 19th amen…

On Saturday, Nov. 5, 1932, just days before the presidential election, Anna Laurens Dawes, 81, known as the "grand lady of Pittsfield," took to the airwaves to urge every Republican to head to the polls that Tuesday.

"Why are we going to vote for Hoover? Because of what he is, and what he has done, and what he is doing, and what he can and will do," she passionately bellowed into the microphone in her radio debut on WGY Springfield.

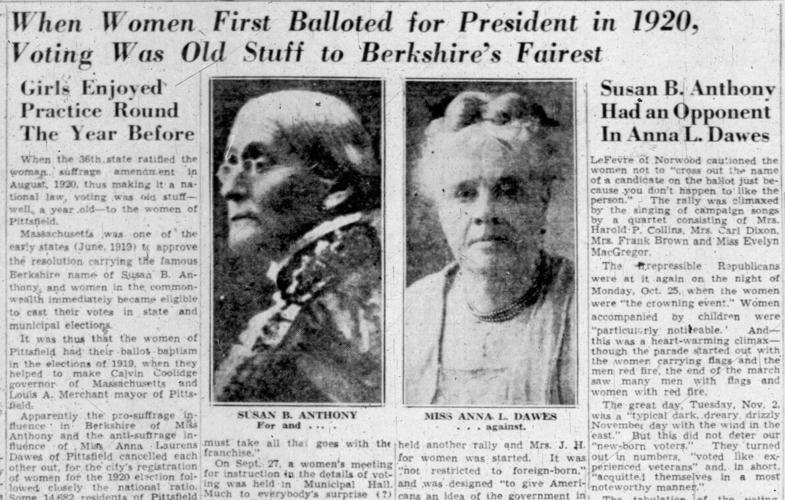

Anna L. Dawes

On the ticket? President Herbert Hoover and the progressive Democratic nominee, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

"This is an election in which every vote counts," she said, urging men, but especially women, to get out to vote.

Being from the Berkshires, birthplace of the most famous suffragette, Susan B. Anthony, Dawes' ardent push for voters to head to the polls doesn't seem out of place — until you consider she, just a dozen years prior, was the leading anti-suffragette of Western Massachusetts, if not the state.

Dawes, in fact, had spent a major portion of her life as an anti-suffragist, serving as vice president of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women from its inception in 1895 until its dissolution in 1919. She was the founder and president of the Berkshires' anti-suffrage society; devoting much of her free time to writing or speaking against the extension of voting rights to women, stating to one reporter that she was of the mind that "feminine nature is unsuited to government."

On Aug. 18,1920, upon learning of Tennessee becoming the 36th state to ratify the "Susan B. Anthony amendment," giving it the required approval of three-fourths of all states, Dawes told reporters she had hoped "women would have a year or two of education in governmental matters before voting for president."

Anna Laurens Dawes's legacy as an anti-suffragist, was noted by The Eagle in November 1940, when marking the 20th anniversary of the 19th amendment and of women voting, legally, in their first presidential election.

Her comments on Susan B. Anthony, to the Wednesday Morning Club, an exclusive literary club she founded, that same afternoon were reportedly limited to "personal reminiscences of her acquaintance with Miss Anthony in Washington, D.C.," calling Anthony "a very pleasing and interesting person." Dawes was said to have "spoke particularly of a bright crimson shawl which [Miss Anthony] habitually wore over a dark dress."

Defeated as she was when it came to the 19th amendment, Dawes was at the front of the line when groups such as the League of Women Voters were formed in Pittsfield.

"The paradox of Miss Dawes was her unmitigated opposition to women's suffrage despite her own great interest in politics and public affairs," The Eagle wrote in a lengthy obituary for Dawes on Sept. 26, 1938. "Miss Dawes addressed many meetings in her futile endeavor to stem the tide. On one occasion, she said that if there were any of her sex still on the fence [about the vote] she would advise them to climb down, for it was a very undignified position. On another occasion, she said [women's suffrage] was one subject on which her mind was absolutely closed, never to be reopened."

Perhaps what made Dawes' opposition to women's suffrage even more confusing was the she was a celebrated author, journalist, activist and an advocate of higher education for women.

Dawes's privileged lifestyle was most likely the cause of her disdain for women's suffrage, according to theories posed by historian Susan E. Marshall, in her book, "Splintered Sisterhood."

"Anti-suffragists organized to protect gendered class interests," Marshall writes. "Most vocal were the wealthy, educated women who exercised considerable political influence through their personal ties to men in politics, as well as through their positions on social service committees."

Marshall is also of the opinion that anti-suffragists "sought to keep the vote from lower class women fearing it would result in an increase of the ignorant vote."

In the case of Dawes, the daughter of an influential U.S. Senator, Marshall's theory has merit.

Born in North Adams in May 1851, Anna Laurens Dawes was the daughter of Electa (Sanderson) and Henry Laurens Dawes. Her father, a prominent lawyer and former editor of the North Adams Transcript, was serving in the state Legislature at the time of her birth. He would move the family to Pittsfield soon after her birth, becoming the state district attorney for western Massachusetts from 1853 to 1857. Henry Dawes would go on to serve as both a U.S. Representative, from 1857 to 1875, and as a U.S. Senator, from 1875 to 1893. (Sen. Dawes would support the creation of Yellowstone National Park; help establish U.S. Fish Commission and daily weather reports to Congress — the early beginnings of U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the National Weather Service — and author the Dawes Act of 1887, which was aimed at assimilating Native Americans into the general population by breaking up the Reservation System and illegalizing Indigenous cultural practices.)

Sen. Dawes political career would play a major role in Anna Dawes's life, giving her access to powerful politicians and families and establishing her as a cultural and societal influencer in Pittsfield and the greater Berkshires for at least six decades.

Anna Dawes first arrived in Washington, D.C., in 1859 at the age of 8, where she attended a reception at the White House for President Abraham Lincoln, who according to reports, scooped her up in his arms and kissed her on her cheek. Lincoln was the first of 11 presidents with whom she would be personally acquainted.

At the age of 20, in 1871, Dawes became a Washington correspondent for the Springfield Republican, the Boston Congregationalist and the Christian Union and later was a regular contributor to several magazines. In 1883, she briefly served as the editor of the miscellany department for the Berkshire Gazette, a weekly edition of the Pittsfield Journal.

Primarily, Dawes worked as her father's personal secretary, spending much of her time dealing with governmental affairs on her father's behalf. In 1883, she lobbied Congress and helped to secure funding for the rescue Lt. Adolphus W. Greely and the members of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition who had been lost in the Arctic for three years. Greely and five survivors of his 25-member crew were rescued in June 1884.

At home, in Pittsfield, Dawes' civic pursuits included saving the Pittsfield Common, as a public park; fighting for the preservation of elm trees along Elm Street and in 1879, establishing the Wednesday Morning Club, a literary club fashioned after Boston's Saturday Morning Club. During her 60-year tenure as the club's president, her connections helped bring in numerous speakers including Woodrow Wilson; Dr. Harry A. Garfield, son of President James A. Garfield; Mark Twain; Robert Frost; and Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and founder of the Tanglewood Music Center. The club's talks, like its membership, were exclusive and not open to the public.

She also served on the state board of managers for the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1892-1894 and on the board of lady managers the St. Louis Exposition of 1902-1904.

Educated at the Maplewood Institute in Pittsfield, and later, the Abbott Academy in Andover, Dawes did not go on to further her education. However, she was a staunch supporter of women's higher education and was a trustee of Smith College from 1889 to 1896. She was one of the first three women to be appointed as a trustee, all of whom were chosen by Smith College's Alumnae Association in 1889.

Anna L. Dawes, 86, just outside First Church in Pittsfield, after attending Easter Mass in 1937.

Dawes was nominated by the Alumnae Association, according to The Smith College Monthly, Vol. 8, 1900, because she was "representing no college but the broader general education gained in her busy, helpful outside life." She would later bequeath a quarter of her residuary estate to Smith College, where a dormitory, Dawes House, still bears her name.

Dawes was also a prolific writer, authoring numerous papers and books throughout her lifetime. Her first book, "How We are Governed," in 1885, was meant to explain the U.S. Constitution and federal government to high school students. She authored "A United State Prison" in 1886; "An Unknown Nation" in 1888 and a biography of U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner in 1892. Her two most prominent works, "The Modern Jew: His Present and his Future," published in 1886, and "The Indian as Citizen," published in 1917, are today, her most controversial due to her opinions. "The Indian as Citizen," written 30 years after the Dawes Act, espouses her belief that her father's bill, had only done good by forcing the assimilation of the Native American with Western society.

Despite her conflicting and often controversial views, Dawes spent her remaining years in her beloved Pittsfield, where she remained a key cultural influencer up until her death, at the age of 87, in 1938.